Contents

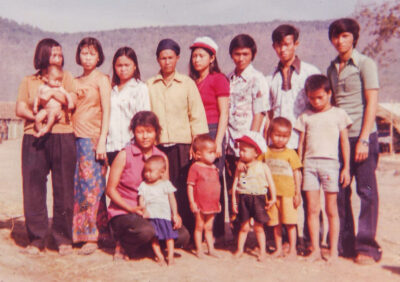

How a Family Survived a War to Tell Its Horrible Story

This is a True Story. Names were given aliases for privacy.

By MICHAEL YUEN | June 1996

CAMBODIA – The burning, hot sun scorched Lily Chan’s eyes while the deadly dry air cracked her tongue. She was craving water and food, but for years, her only source of energy came from eating ants, spiders, certain kinds of leaves, snails, rats, and many other disgusting creatures. Her other option was to eat human flesh, but despite the hunger, she refused to even touch dead people who had died from either malnutrition, disease, or the surrounding land mines.

Chan was born from a Chinese family who had moved to Cambodia, possibly after the year 1930. However, at the outbreak of the Cambodian civil war, she and her family were robbed of all their money, jewelry, and other possessions.

“What happened then?” I asked in her native language, Dongguan, a dialect spoken in the Hong Kong area and its surroundings, which is similar to Cantonese, also a Chinese dialect.

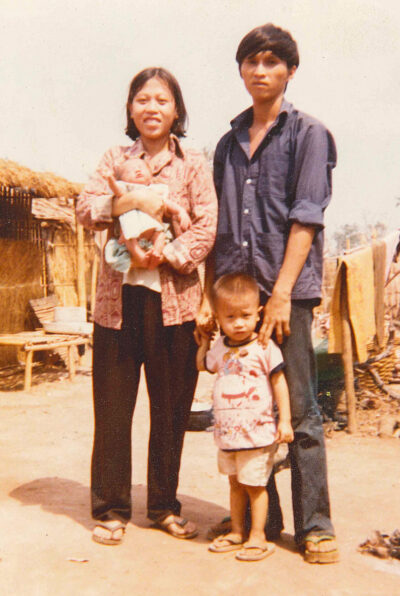

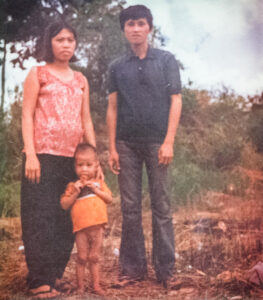

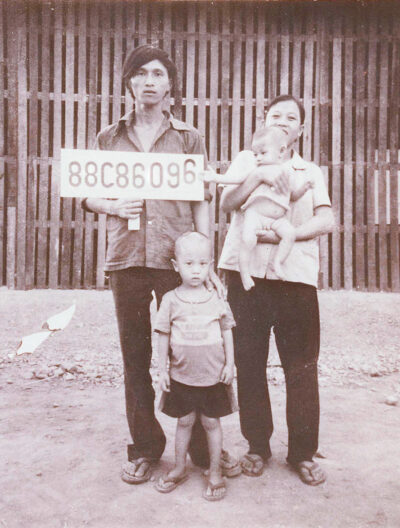

“We became… poor beggars after our business was destroyed. Sadly, I had to find a husband as soon as possible because any unmarried woman was allowed to be raped by soldiers. I was only seventeen then.” I later learned, during the interview, that her husband, John Woo, was an almost complete stranger to the family before their wedding. Their marriage had been arranged by their respective parents without having asked their respective children if they were willing to marry each other. In fact, she and John had never met each other before until their wedding. “He was not a good husband,” she said, refusing to reveal more information about him. “He’s better now, though.” Soon, when Lily was eighteen years old, her first son was born.

“Tell me more about your attempts to reach safety in nearby Thailand.”

“It was a long, agonizing march. We constantly had to try to avoid enemies, while searching for land mines and other deadly traps.” Additionally, her first son, now three years old, and an unborn one in her stomach, added more to her struggle to stay alive. “We reached [the Thailand border] once, and the [Thai] soldiers, who were patrolling there, brought us on a bus and told us that they were going to bring us to a safer place in another country.”

“You must have felt lucky then?” I asked enthusiastically, thinking that her flight was over.

“No, not at all. I became concerned when the bus stopped to fill up with gasoline. An employee for the gas station had whispered to me that it was going to be a long ride and that I should use the food and water sparingly. He didn’t tell me where the soldiers were really bringing us. He seemed to be scared to tell me. Nobody, but the soldiers in the bus, knew where we were going.

“Days later, when we were left at the top of a hill, we learned that we were still in Cambodia. The hill was bloody and full of dead bodies; we saw land mines everywhere. In fact, all refugees who arrived in Thailand were deported there; yet, I still don’t know why the Thai wanted all people to get killed on that [death-bringing] hill. I suspect the Thai government was behind that.

“They [the soldiers] forced us to go downhill, but as soon as a man exploded, all of us turned and ran back towards the bus. Everybody was screaming, but the soldiers ruthlessly machine-gunned down many of us.” She showed me how the soldiers were shooting the people. It was just as if they were mowing grass with their weapons. Lily continued, “We immediately headed back down the hill. Though there were only a few, some Vietnamese soldiers [prisoners-of-war], who were also captured by the Thai, used their skill to de-activate some land mines during the horrible trip. The thought of exploding gave us immeasurable fear, especially when we saw people [detonate] near us.”

Unknowingly, her eyes turned into those of disgust. I believed that she had remembered something, for her eyes became red, accompanied by some tears. She started to tell me about some dead people that were on the hill, even though the story did not relate to her attempt to reach Thailand: “Worms were crawling in and out of their bodies. I remember how I once saw a mother, who had exploded from a land mine, lying motionlessly beside her baby. She was dead and worms were already feeding on her. The baby was sitting upright and was alive and conscious, yet it did not cry nor move.” I was listening cautiously, and learned that the baby was also covered by the worms that had come from its mother. They were crawling on the zombie-like infant like a colony of hungry ants dissecting their victims. “Some [worms] had dug into the baby’s skin and some others had come out of its body. The child’s nose, ears, and other places were filled with those white worms, yet the baby did not move; only the eyelids did,” Lily said as she started to cry more heavily. Her body was shaking as if she was cold, making me feel very sorry for her. I felt my eyes narrowing while my vision started to blur as if I was under water. Clearly, re-living her life was unpleasant for both of us.

As she described, they did not have any container to store water nor food. They were forced to eat until they “dropped” when opportunity came, though these “happy” occasions came rarely. I could not imagine her eating rats, tarantulas, ants, and other animals. As an example, she said that she took a branch, inserted it into an opening of an ant’s colony, took it out, and licked the branch, with the ants on it, as if she was holding a stick of ice cream. As one can imagine, some of the ants, ones that did not get caught in the mouth’s slimy saliva, “tickled” her tongue and mouth. Most often, she ate things raw, including worms and bugs.

“Once in a while,” she proceeded, “my husband and I were able to find a temporary job. But the pay was not high enough to feed our family.” They had to find another way to satisfy their need. “Many nights, we sneaked out of our huts and successfully stole rice from our boss. One night, my husband was caught in the act, and was facing our boss at gunpoint. I had to run away towards our hut to save my own life, but could not stop to see what was happening to my husband. I was in great fear for both of us and cried when I did not see him return for a long time, even though it must have only been a couple hours when I saw him finally come back to our hut.”

Her husband, who was sitting next to her, had quietly been listening to her story as he suddenly opened his mouth. He said, “I was questioned about why I had come to steal. I said that I was hungry. Later, the boss asked me if I was a spy for the enemy. I said, ‘No.’ ‘Did you steal the rice so that you can sell it?’ was his next question. ‘No,’ was my answer again, and I said it once more when I was asked if my supervisor had instructed me to steal the rice for him. I was saved from being killed when my supervisor told our boss that I was a good worker. My punishment was to work for the boss for three days without pay, but my family was well-fed in the meantime. We even had dessert!”

Pausing briefly and looking down at the floor, then back at me, he continued, “I was almost executed. I owe my life to my supervisor.” With that, I saw his eyes turn red and wet, just like his wife’s. I had never seen him in that state before. He had never cried nor had he ever shown that he was about to. In fact, I had never seen him cry or turn sad before. Able to imagine that they had been willing to risk their lives for food, I realized how bad and sad Cambodia must have really been for them. What else could have caused a tough man like John to almost cry?

When it came to water, Lily’s family had to scoop dirty, often bloody water, when they were lucky to even find some liquid. “I had even drunk from dirty water that was infested with white worms,” Lily said. I asked her about what kind of worms they were; they were the same worms that feed on dead bodies. If no fluid was available, she had to force herself to drink her own urine.

Lily’s family was walking down the hill at an average of eighteen miles a day. Compared to the Los Angeles Marathon of, I believe, twenty-two miles [it is 26.2], one can imagine how many miles eighteen are. However, her family had to have greater endurance than the participants of the Marathon, for there were several additional factors acting against the Woos. They were: the hot atmosphere and the sun, hunger, thirst, constant fear of meeting enemies, and the fear of stepping on a deadly trap.

She did not want to tell me more about what happened during her march back down the hill, but she did say that she had lost a nephew during an explosion.

“After you reached the bottom of the hill, did you try to go back to Thailand?”

“Yes, definitely,” she answered. “My unborn child was already growing big. I do not know how many months he was already, but I was very tired of having to take care of my first child and the unborn one. My husband did not have the time to help me out all the time, for he had to go look for food and water. My problems ended when we reached Thailand again. This time, we arrived at a Red Cross refugee camp. They took good care of us. Months later, my second child was born healthy.”

“Can you tell me what life was like when you were a beggar?” I asked her.

After a brief silence, she replied, “I was once able to beg for a tiny bowl of rice soup. I fed my first child first, while my husband’s and my stomach were growling crazily. After having given most of the rice to the baby [referring to the first child], I wanted to taste some. The baby began to cry wildly when it saw the spoon near my mouth. Out of embarrassment [they were surrounded by people], I continued to feed my child. My husband and I continued to starve.” At this moment, I was about to cry, but I held back the tears so that I wouldn’t disturb the interview.

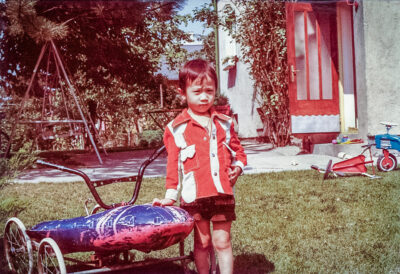

“Because of this [and many other difficulties],” she resumed, “I once wanted to give my baby to a rich person so that at least he [the first child] could survive and have a better life. I did not give him away though; my parents [and brother, Chaney] were yelling at me not to. ‘You might need him later in your life [and if we die, we die together],’ they said. As beggars, so many things happened to us. People spat on us, called us names, stoned us with disgust, beat us with canes, and many other things.”

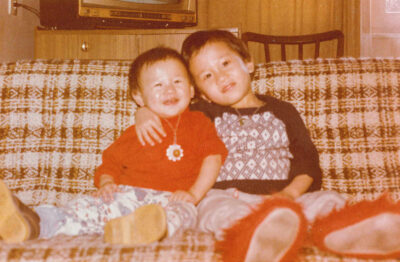

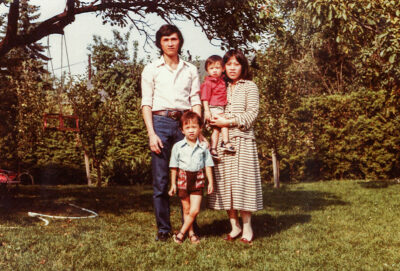

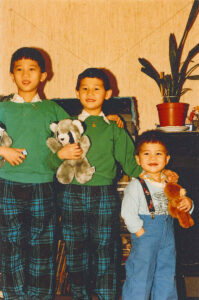

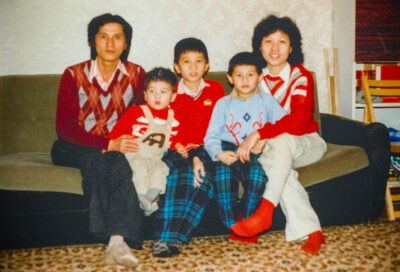

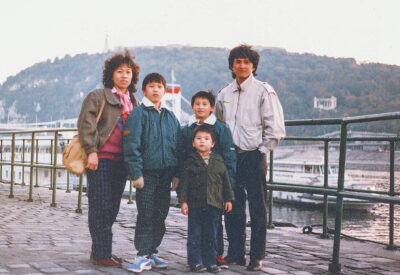

After getting her first offer to go to Austria, she immediately accepted it, for she did not know if such an opportunity to go out of the war zone would ever come again. While having to endure prejudice from Austrians towards the Chinese, she lived there with her family for eleven years, while working as a janitor and housekeeper. Her husband switched jobs many times, but was mainly a painter and carpenter. Her third son was born in 1984, her first child to be born in a sophisticated hospital. “My first son was still suffering from the war. His grades were not good and my friends said that he would never make it through elementary school. When very good friends of mine, Maria and Marcel, among others, offered to help him, he gradually improved. And this moment I will never forget: he laughed for the first time when he received a number “1” [grade “A”] for most of his school classes. After twelve years I finally saw my son laugh! That’s when he finally started to get better and better in school. I was very proud of him when he received his first academic High Honor in the eighth grade, the last year before we were allowed to immigrate into the United States. My second son also did well [with the help of the same friends].”

“When did you move to California?”

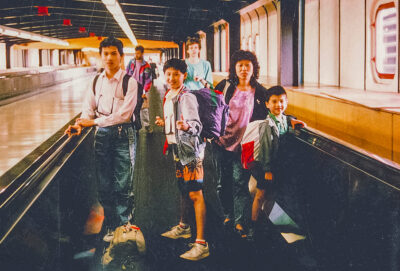

“In 1991.”

“And as I can see, you are now permanently working in a donut shop while your husband bakes donuts at nights?”

“Correct,” she replied with a smile. I was happy to see her smile. It was better than seeing her cry just moments ago. “My first son is going to Fullerton Community College now, the second in the tenth grade, the third in the sixth grade. I am quite happy with my life, though we still have financial problems. Hopefully, business will pick up soon.”

Her first son is the first in the family to have passed the fourth grade and, therefore, also the first to attend a college. Additionally, he will be the first to learn how to read and write Chinese, if he can get into the always-full Chinese 101 class next semester.

“I thank both of you for having taken your time for the interview. I really appreciate it.”

“You are welcome,” was their last reply.

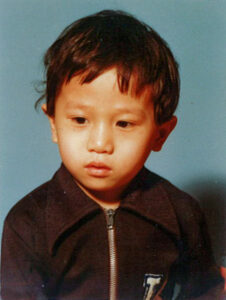

Lily Chan’s life story intrigues me because she showed courage and fear, overcame great hunger and thirst, and expressed love to keep the family together and alive. Despite her illiteracy, she speaks Chinese, Cambodian, German, English, and Spanish, talents that I, currently, cannot match. Though her family and she are still suffering from economic problems, I can also be proud of her. I know that I am very pleased with her success, for I, Michael Yuen, am her first son.

Mom and Dad, I love you both (and my brothers)!

“Some people suffer in silence louder than others complain.”

(The Lion, Lions Club International)

Many, many, many thanks to the grandparents for their love, wisdom, strength, and generosity.

Did You Know?

- Michael was born in the Cambodian jungle during the war and nearly died from an unidentified disease

- A Good Samaritan soldier provided him with life-saving medicine after seeing his lifeless body

- Many Cambodian refugees opened Donut Shops throughout California, driving out established corporations like Winchell’s and Dunkin’ Donuts

- Watch The Donut King (2020) (IMDb) – one of the Cast members is related to our family

- Why are Donut boxes pink?

About the Cambodian Genocide

Publication

This story was originally published, upon recommendation by the author’s English professor, in the Fullerton College, “The Hornet”, newsletter in shortened form in June 1996. A copy can also be found at: https://www.yuenStudios.com/story.